Highway History: The brief, controversial life of Grand Canyon Bridge

Highway History: The brief, controversial life of Grand Canyon Bridge

By Steve Elliott / ADOT Communications

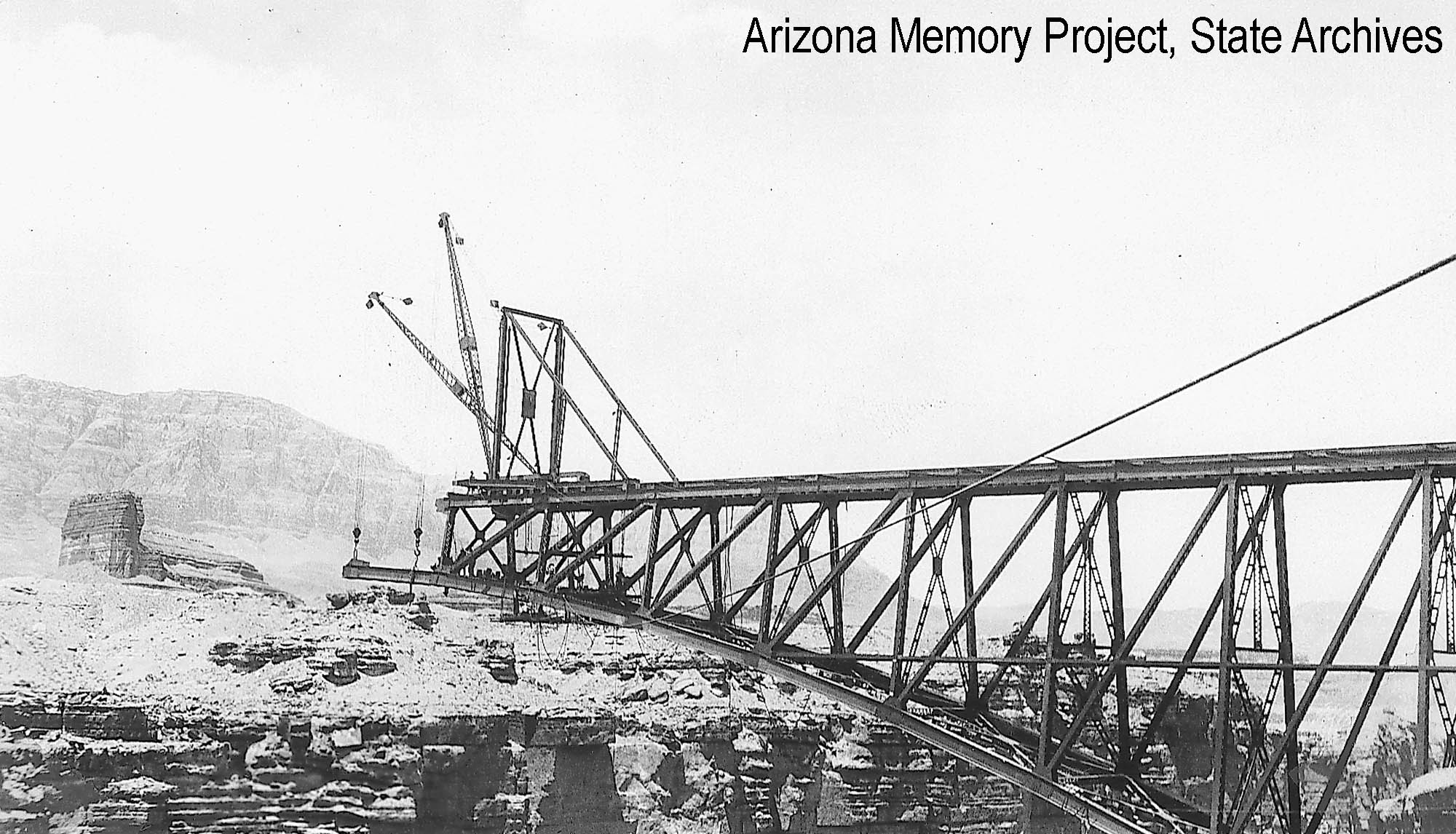

Arizona Governor John C. Phillips hailed it as a feat of “creative genius and daring.” Thousands, including the Winslow High School marching band and governors of Utah, New Mexico and Nevada, made long trips to help Governor Phillips and a host of other dignitaries dedicate it on June 14-15, 1929. Its name inspired awe: Grand Canyon Bridge.

“Man has achieved another triumph over grim nature,” Governor Phillips told those assembled next to this bridge traveling high above the abyss. According to The Arizona Republican, as the newspaper was known at the time, Elizabeth Phillips, the governor’s daughter, christened Grand Canyon Bridge with a bottle of Colorado River water.

Just a few years after this grand celebration, however, Grand Canyon Bridge was no more.

I’m setting you up, of course. What Governor Phillips dedicated as Grand Canyon Bridge never carried vehicles over the Grand Canyon proper. And it’s still around, though with a different name assigned in 1934: Navajo Bridge. Spanning Marble Canyon in far northern Arizona, the original Navajo Bridge stands next to a newer Navajo Bridge that since 1995 has carried US 89A over the Colorado River.

Much has been written about the feats of engineering and bravery behind Navajo Bridge, which created a long-sought highway link with Utah across the Colorado River. But for years before, during and after construction a surprising amount of attention and argument focused on its name. Two governors, state lawmakers, a noted northern Arizona pioneer, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, the head of the National Park Service and the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were among those drawn into the fray.

Pretty much no one else appeared to have been satisfied when the State Highway Commission voted on Nov. 14, 1928, to formalize the name Grand Canyon Bridge. Minutes from that meeting noted that “many protests were read” and “numerous names suggested.” Still, commissioners decided “this name will mean much more to Arizona on account of the Grand Canyon being so widely advertised.”

Moves began quickly to find a different name for Grand Canyon Bridge.

An obvious argument against that name focused on geography. Narrow Marble Canyon, which is grand in its own right and today is part of Grand Canyon National Park, is quite distinct from the mile-deep, miles-wide splendor of the Grand Canyon beginning quite a ways down the Colorado River. In one of the arguments along this line, Horace M. Albright, director of the National Park Service, sent Governor Phillips a letter in February 1929 saying the name Grand Canyon Bridge could leave motorists mistakenly thinking they’d passed over the Grand Canyon.

“He might feel that the ‘Grand Canyon’ as he saw it did not come up to his expectations and it would be unnecessary to make the trip either to Bright Angel Point on the North Rim or El Tovar on the South Rim because he had already seen the ‘Grand Canyon’ by crossing the Grand Canyon Bridge,” the letter said. Albright didn’t recommend a different name but said his agency “is simply calling this situation to attention for proper consideration.”

According to The Arizona Republican, Governor Phillips, who had just taken office in early 1929, responded that he too disagreed with the name Grand Canyon Bridge and would ask commissioners to come up with a new name before the dedication. Yet the name stayed through the end of his time as governor in 1931 and through the two years after George W.P. Hunt defeated Phillips and returned to the governor's office.

Much of the early momentum against Grand Canyon Bridge came from people who preferred the name popularized when spanning Marble Canyon was just an idea: Lees Ferry Bridge, a nod to the historic Colorado River ferry crossing several miles upstream. As The Arizona Republican said in its coverage of the debate, “The bridge always has been known and is still known throughout the state as ‘Lee’s Ferry Bridge.’” Several of the many ads in the Grand Canyon Bridge official dedication program, posted by the State of Arizona Research Library's Arizona Memory Project, referred to Lees Ferry Bridge. (Note: Since its founding in 1890, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names has discouraged the use of apostrophes in possessives, which is why I use Lees Ferry here except when Lee's Ferry appears in a quote.)

Brandy Helewa, Discovery Librarian for the State of Arizona Research Library, kindly shared articles and documents on moves to formally change the name to Lees Ferry Bridge and the arguments against doing so. These included The Coconino Sun’s account of acid letters to the Highway Commission from Timothy Allen Riordan, part of the pioneer family behind Riordan Mansion State Historic Park and President of Arizona Lumber & Timber Co. in Flagstaff.

“All the pioneers of this state knew Lees Ferry and they knew it long before my coming to the territory over forty years ago,” said one of Riordan’s letters, penned shortly after the Highway Commission’s decision, “and if this name is not attached to the new bridge the result will be that in a very few years the tradition of Lees Ferry will have passed away …

“A tradition is a sacred thing, a beautiful thing, and to disturb it is like disturbing a grave,” Riordan continued. “Men of fine feeling resent it and regard it as the work of ghouls.”

In early 1929, months before the dedication, the state Legislature considered a bill that would have changed the name to Lees Ferry Bridge. That didn’t sit well with Heber J. Grant, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, who, while vacationing in Los Angeles, traveled to Phoenix to tell state lawmakers and highway commissioners that the name Lees Ferry Bridge would “reflect on all the Mormon people in every land and every clime.” That's because John D. Lee, who founded the ferry in the 1870s, became the only person convicted — and executed — for the 1857 Mountain Meadows Massacre in Utah Territory.

Addressing the Highway Commission, Grant suggested that if the bridge should be renamed it could be called Hamblin-Hastele Bridge to honor LDS pioneer Jacob Hamblin and Chief Hastele, with whom Hamblin was said to have achieved goodwill with the Navajo people. According to meeting minutes for March 5, 1929, commissioners voted to convey their wish that the bill be indefinitely postponed. While the legislation passed the Senate, it was amended in the House to name the bridge Hamblin-Hastele and foundered without resolution.

The Arizona Memory Project has correspondence dated March 5, 1929, in which former state historian James McClintock, who was Phoenix postmaster at the time, says he had suggested Hamblin Bridge to Grant as a way of beating back the push for Lees Ferry Bridge. McClintock’s letter said that Grant also would accept Navajo Bridge or Marble Canyon Bridge, though no change was recorded until nearly five years later.

A visit to the State of Arizona Research Library helped me flesh out what finally led to agreement on a new name: a flurry of letters in the second half of 1933 centering on Governor Benjamin Baker “B.B.” Moeur, who took office in January of that year.

Following up on correspondence earlier that year between Governor Moeur and the Acting Commissioner of Indian Affairs on renaming the bridge, U.S. Interior Secretary Harold L. Ickes noted that “Indian funds” were used for construction ($100,000 of the $390,000 came from the Navajo Tribal Fund, according to ADOT’s Historic Bridge Inventory). Because of that, Ickes said, his department should have a say in the name.

Governor Moeur’s secretary replied on his behalf: “Arizona is fortunate indeed to have the bridge and the Governor feels that it is entirely within your province to select whatever name is desired for the same.” But when Ickes responded that he preferred Lees Ferry Bridge “because of its historical significance,” Heber J. Grant entered the story again. Governor Moeur’s reply noted the LDS President’s opposition to Lees Ferry Bridge, as related by the Highway Commission, and suggested on behalf of the commission switching to Marble Canyon Bridge. That prompted Ickes to appeal yet again for Lees Ferry Bridge: “I wonder if we could persuade President Grant of the Mormon Church to withdraw his objection to the use of this name?”

Governor Moeur then wrote Grant to convey Ickes’ request, prompting a long response from the LDS President. Grant agreed that Grand Canyon Bridge should go because of the geographic confusion. But he continued to object to Lees Ferry Bridge for reasons including Lee’s place in history, the bridge’s distance from the ferry site and the availability of what Grant suggested as better options honoring Jacob Hamblin or Chief Hastele or both. Grant urged Governor Moeur not to sanction changing the name to Lees Ferry Bridge until he could speak with him personally.

“Name it after one of the Governors of Arizona, call it Marble Canyon Bridge since it crosses Marble Canyon, or call it the Kaibab Bridge, because it permits you to go to the Kaibab Forest,” Grant continued, suggesting he’d be fine with pretty much anything but Lees Ferry Bridge.

Meanwhile, this letter opened the door for a suitable alternative, with Grant noting that one of his counselors had suggested Navajo Bridge if other options the church favored weren’t acceptable.

When Governor Moeur shared Grant’s response, Ickes replied to say that while he still would prefer Lees Ferry Bridge “because it is historic and characteristic,” he had no objection to Navajo Bridge. “This seems to be Mr. Grant’s second choice and if this is also agreeable to you I am convinced it would be a satisfactory name,” Ickes wrote.

Done deal.

Highway Commission minutes in early 1934 noted that Governor Moeur had sent a letter “referring to the much discussed name for the bridge over Marble Canyon” and suggesting Navajo Bridge “inasmuch as the name ‘Navajo Bridge’ meets with the approval of the Secretary of the Interior, the Indian Service, and Honorable Heber J. Grant, President of the Mormon Church.”

The commission voted in favor of the change and requested “the necessary steps be taken by the Engineering Department to change the name of the bridge to ‘Navajo Bridge’ and, when funds are available, a suitable plaque showing the new name be substituted for the present one on the bridge.”

Today, Navajo Bridge seems the perfect name for this structure framed by the Navajo Nation’s Echo Cliffs to the east, the Vermilion Cliffs to the west and the river below. Its brief history as Grand Canyon Bridge is but a footnote nearly a century later, while the battle over its name lives deep in the archives. It seems odd to think this bridge, which visitors now cross on foot, many of them on their way to and from the Grand Canyon, ever had the name Grand Canyon Bridge, or that it came very close to being called Lees Ferry Bridge, Hamblin-Hastele Bridge, Marble Canyon Bridge or anything other than Navajo Bridge.