Leslie Creek bridge sits on the edge of the state and history

Leslie Creek bridge sits on the edge of the state and history

Leslie Creek bridge sits on the edge of the state and history

Leslie Creek bridge sits on the edge of the state and history

Today, determining jurisdiction is pretty simple. ADOT oversees all state highways and freeways, with individual counties and municipalities taking care of the local infrastructure that falls inside their boundaries. But in the early days of transportation, such things were still being worked out.

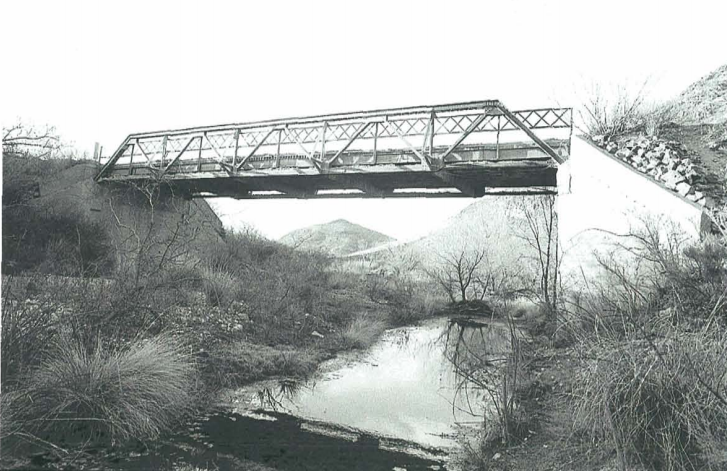

And that brings us to the Leslie Creek Bridge. Located along Leslie Canyon Road in Cochise County roughly 17 miles north of State Route 80 near Douglas, this bridge is going on 93 years and is listed on our inventory of historic bridges in the county.

The origins of this 70-foot bridge goes back to 1928, when the Cochise County Board of Supervisors approved its construction. Chosen to make the parts that would eventually become the Leslie Creek Bridge was the Virginia Bridge & Iron Company, which made bridges across the country during this time. For this particular location, a truss comprised of 10 equal-length panels, with verticals at the panel points, was made. These fabricated parts were then shipped to Arizona via rail in May 1928. Construction got going almost immediatley using prison labor, which wasn't that uncommon at the time. The bridge was done by the end of that summer and has been functioning since. It was also a fairly common design for the times. In fact, the Leslie Creek Bridge is one of eight in the inventory with virtually the same structure.

That's all well and good, you might say, but this is an ADOT blog, so why are we talking about a county bridge nowhere near a state highway?

Because the Leslie Creek Bridge was built at an unusual time. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, local governments often took lead in establishing roads, bridges and other infrastructure. By the time the span over Leslie Creek was done, the Arizona Highway Department - the precursor to ADOT - had taken over the main responsibility for building bridges statewide. However, individual counties would still sometimes do smaller projects just as they always had. This particular bridge is one of the later examples of a county-built bridge, purchased in prefabricated parts from a national bridge company, and constructed by local crews.

And, hey, it seemed to work. Having a bridge just shy of a century is pretty impressive, no matter the size or where it's located!