Highway History: The 9-year-old who dedicated Roosevelt Lake Bridge

Highway History: The 9-year-old who dedicated Roosevelt Lake Bridge

Highway History: The 9-year-old who dedicated Roosevelt Lake Bridge

Highway History: The 9-year-old who dedicated Roosevelt Lake Bridge

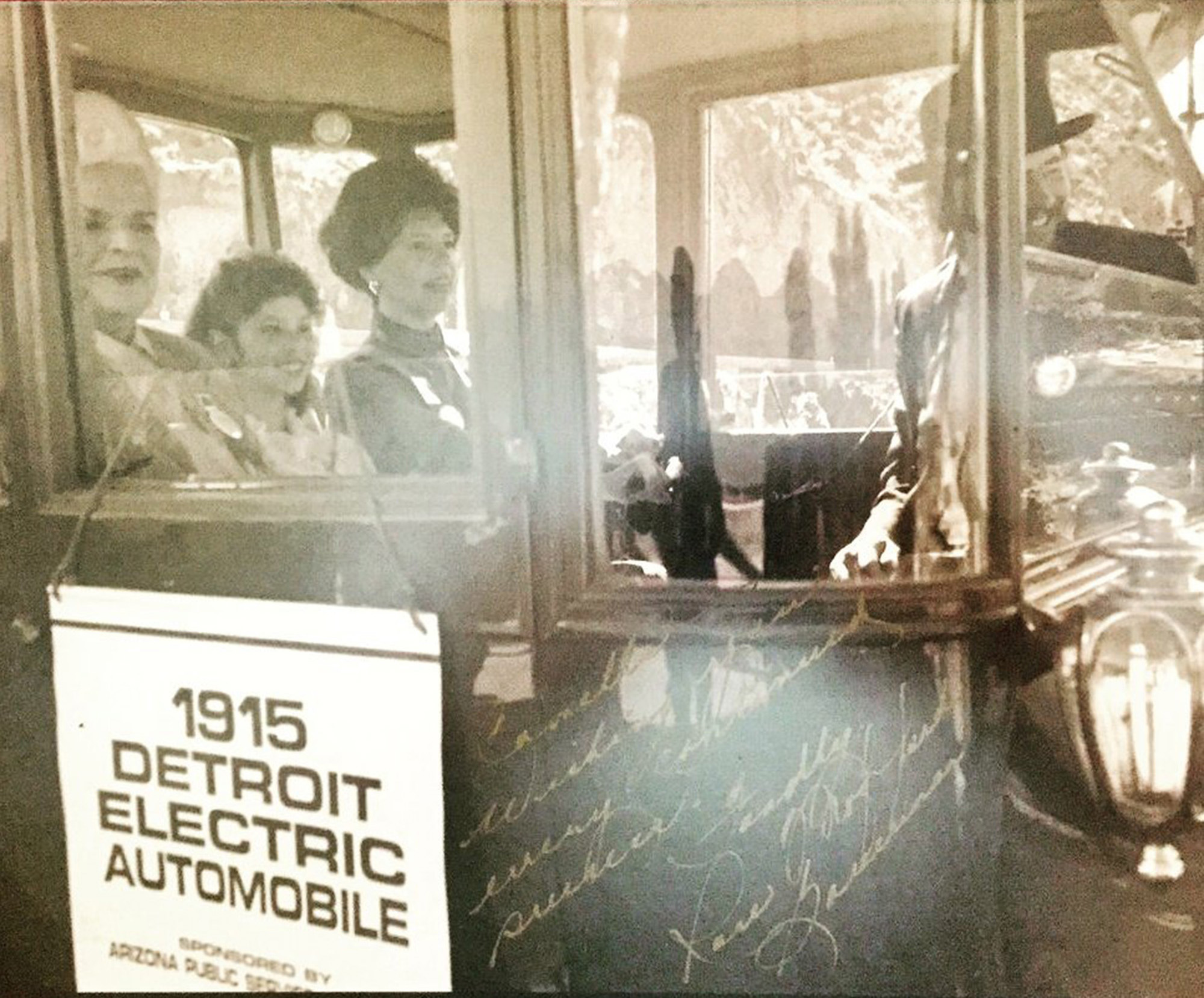

Around 3,000 people gathered Oct. 23, 1990, to dedicate Roosevelt Lake Bridge on State Route 188, and none had a better seat than 9-year-old Carmelle Malkovich of Claypool.

Malkovich got to join Governor Rose Mofford on the first trip across the bridge by winning a Globe-Miami Chamber of Commerce raffle. That’s her in the photo above, riding in a 1915 electric car flanked by Governor Mofford and a representative of Arizona Public Service.

Thanks to LinkedIn, I recently caught up with Malkovich, who today is Director of Communications for Dignity Health in Arizona and Nevada. She graciously shared her memories of that day, including the way Governor Mofford put her at ease during an event that drew numerous VIPs and reporters.

“She couldn’t have been any kinder and nicer to me,” Malkovich said.

Governor Mofford shared her fondness for Malkovich’s grandparents, whom she knew because the governor too hailed from the Globe-Miami area. The two also had a shared Slavic heritage – Croatian for Mofford and Serbian for Malkovich.

“She did very much inspire me,” Malkovich said. “She really demonstrated that day how a young Slavic girl from a small copper-mining town like her can really achieve anything.”

And then there was the magnificent 1,080-foot-long arch carrying State Route 188 over Roosevelt Lake. Roosevelt Lake Bridge remains the nation’s longest two-lane, single-span steel through arch bridge.

“I remember seeing this huge, beautiful bridge,” Malkovich said. “I remember watching the progress of the bridge being built, but I don’t think I realized at the time just how big and how beautiful it was going to be.”

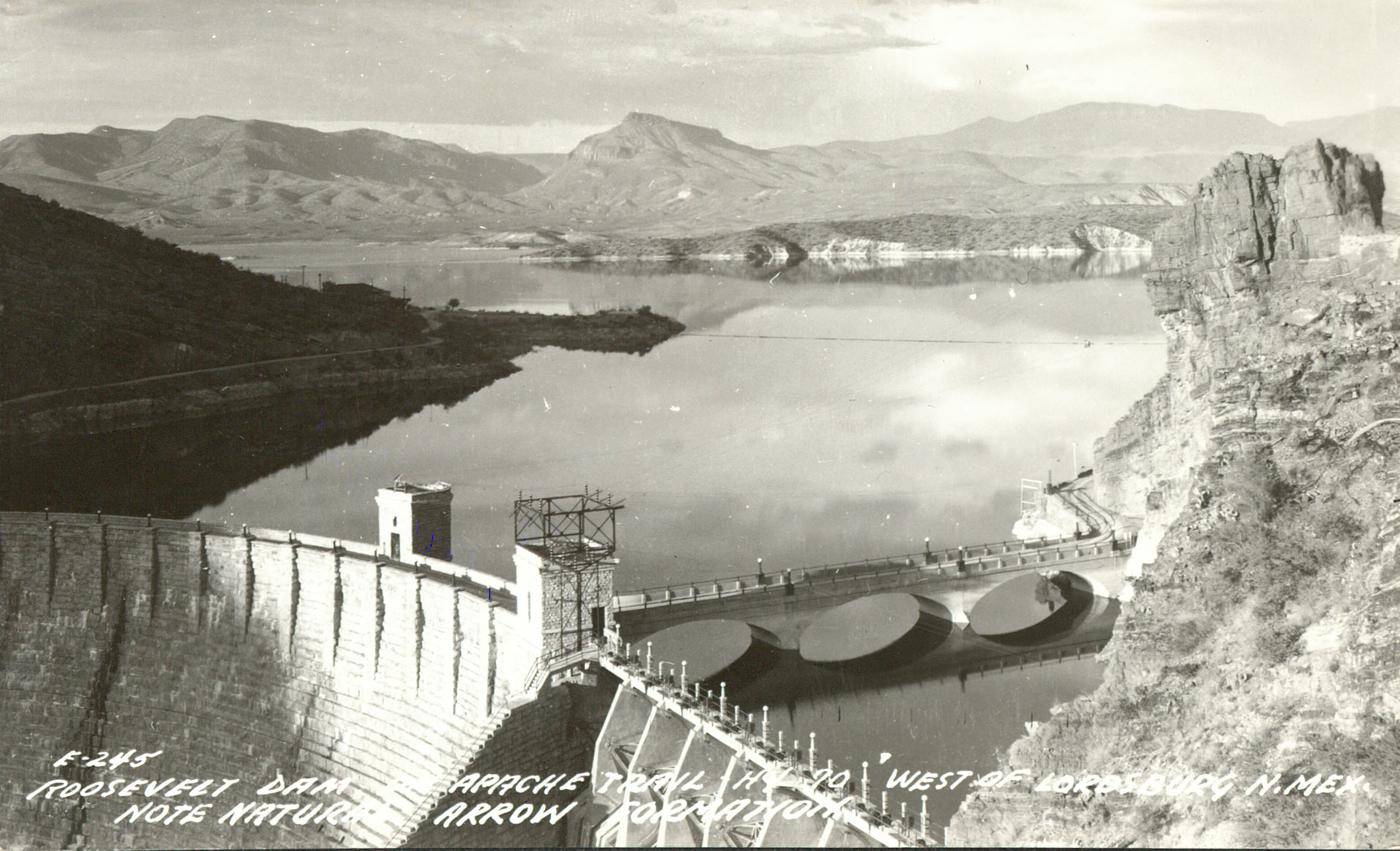

With Malkovich helping cut the ribbon to open the bridge, Governor Mofford and others celebrated a far more efficient path for SR 188 at Roosevelt Lake and between the Gila County communities of Globe and Payson. Traffic had been winding down to and then crossing one direction at a time atop the original Roosevelt Dam, which was soon to be replaced by a larger dam when the bridge was dedicated.

Governor Mofford told the crowd: “People in Gila County will no longer feel separated by northern and southern sections.”

Even at such a young age, Malkovich knew she was doing something very special. “I remember my dad telling me how historic this was and to really be honored to be a part of it,” she said. The photo above still hangs in her parents’ house in Claypool.

The experience made Malkovich a bit of a celebrity in her hometown. The owner of a local Mexican restaurant made her a jacket – blue, like the bridge’s arch – with “First to Cross the Bridge” on the back in pink letters.

“I’ll go home to my parents and I still get stopped by people in town who will say, ‘I remember when you were the first to cross the bridge,’” Malkovich said.

About a decade after the dedication, Malkovich got to experience the bridge’s benefits, along with a heavy dose of nostalgia, when she crossed it on her way to and from Northern Arizona University.

“It really connected us to Roosevelt, to Payson and to northern Arizona,” she said.

It's been a few years since Malkovich has visited the bridge, but it continues to impress her long after that first trip across.

“It’s just beautiful, and the landscape out there is gorgeous too,” she said. “It fits just perfectly.”